By Sophie Girard

Writer, poet and playwright Cherríe Moraga has received UC Santa Barbara’s annual Luis Leal Award for Distinction in Chicano and Latino Literature, for giving voice in her work to those who are marginalized and overlooked.

“My job is to look for what’s missing in the picture, whatever the picture is,” Moraga said at a talk she gave earlier this month after receiving her award at an event hosted by the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center.

Cherríe Moraga, author, poet, and playwright, is the recipient of UC Santa Barbara’s Luis Leal Award for her contributions to Chicano and Latino literature.

Moraga, a UCSB professor of English and co-director of Las Maestras Center for Xicana Thought, Art, and Social Practice, spoke to a large audience about her upbringing and her experiences as an activist for La Red Xicana Indígena, a social justice organization to raise awareness about Indigenous life and rights.

She started her speech by acknowledging the Chumash people, the tribe indigenous to Santa Barbara and other coastal regions in California.

“Before I came, I walked out to the ocean, so I remembered where I was. I remembered that this is old land, old water,” Moraga said. “I remembered my relatives, my sisters and brothers, the Chumash people that came before, that are here now.”

Moraga is the author of many works, including This Bridge Called My Back, co-edited with Gloria Anzaldua, Loving in the War Years, The Last Generation, and The Native Country of the Heart. Among the awards she has received are the Brudner Prize, the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies Scholars Award, the first annual Cara Award, and the United States Artist Rockefeller Fellowship for Literature.

Her latest award is named for the late Luis Leal, a professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at UC Santa Barbara who was internationally recognized as a leading scholar of Chicano and Latino literature.

Moraga said she grew into storytelling and writing during her childhood in Los Angeles, having acquired a love of writing from her family. “I love literature because my sister read to me. My family were great cuentistas. They were great storytellers," she said.

Until college, Moraga struggled with reading. Propelled into an existential crisis when she left Catholicism, Moraga turned to books as a solution and started learning through them.

“I wanted to know the meaning of life, as weird as that sounds,” Moraga said.“Because Catholicism wasn’t the meaning of life. It had betrayed me so many times in so many ways, from its notion of what women are and its notion of heterosexuality.”

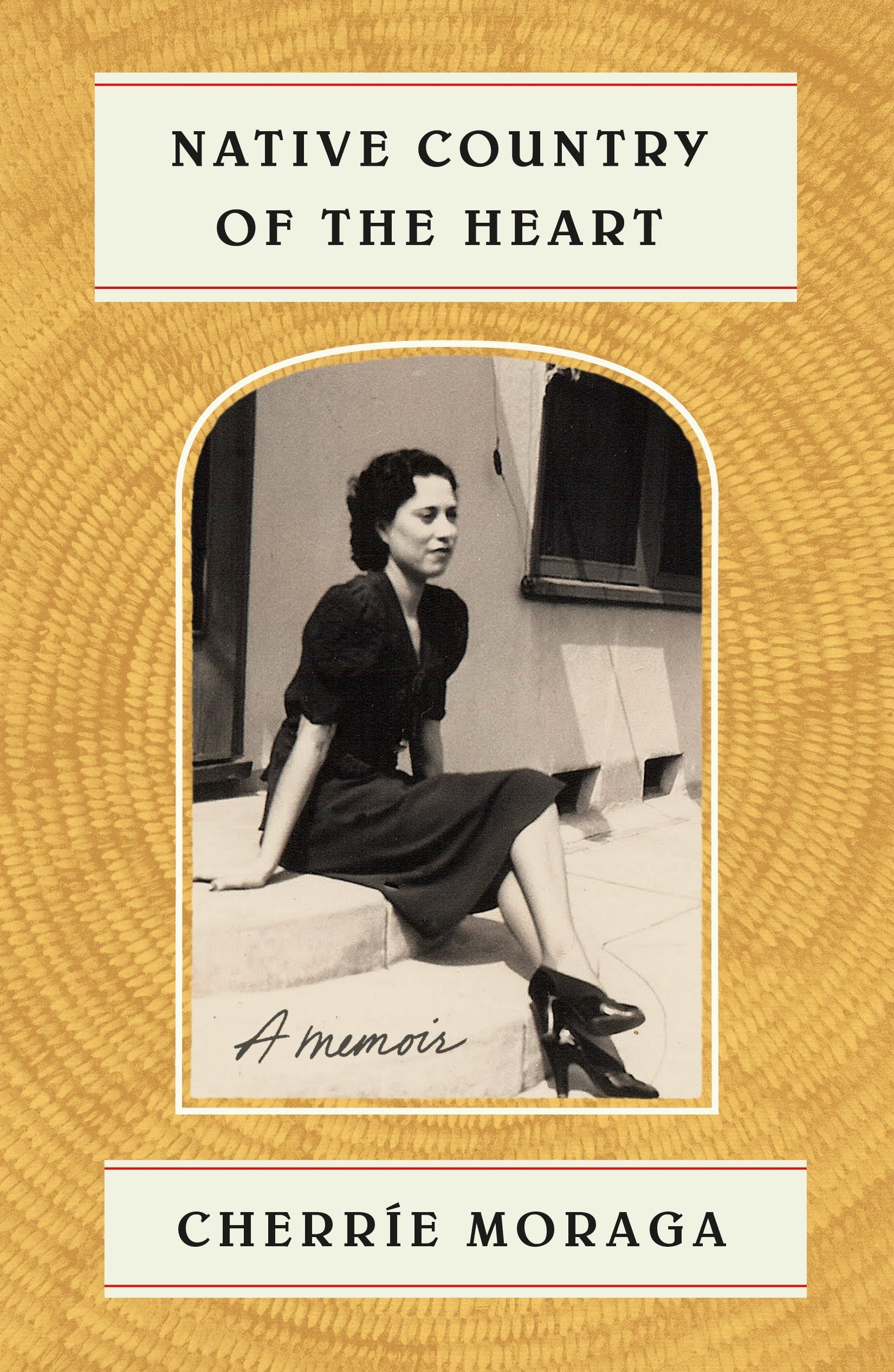

Cherríe Moraga’s memoir Native Country of the Heart. Moraga co-directs UCSB’s Las Maestras Center.

Moraga explored her feelings about the Catholic Church in her poem “Elvira's Country,” which is part of her memoir Native Country of the Heart. The memoir describes her mother Elvira’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease, and delves into Moraga’s experiences with Catholicism and the Mexican American diaspora. “If the Church said my mother was a sinner, there was something wrong with the Church,” Moraga said, reading from the poem.

Moraga’s memoir follows Elvira from a young age, describing how she grew up in California working in agriculture and later moved to Tijuana. She married a white man and started a family in Los Angeles. Moraga highlights the complexities of her and her mother’s relationship, as well as Moraga’s journey to connect with her roots and coming out as lesbian.

Moraga’s relationship with her mother also shaped her views on sexism. Moraga said she felt betrayed by her mother’s double standards. “I would have to admit that my mother had two faces, that you couldn't always count on her. My mother sold my sister and me out all the time to my brother,” Moraga said. "It's been built into the Mexican female psyche that we are traitors."

Moraga believes the political role of writers and artists is to speak from one’s heart. "It’s to be able to respond to what's most evident without footnotes," she said, with no need to always rationalize everything they create. “What's being generated is largely coming from their conscience,” Moraga said. “It can't always be explained. Once you try to explain it, you've killed it."

When it comes to speaking from the heart, Moraga said that’s how she came up with the title of the memoir, Native Country of the Heart. Instead of searching for a title, she found that the title was a result of the writing. “The writing will tell you what it wants to be. It will finally reveal back to you what you really need to say,” said Moraga.

Moraga spent 35 years writing the memoir. As she was grieving her mother’s passing, she realized that her strength came from her love for her son and community. “I know that there is a heart in here that has some relationship to land, some relationship to place, some relationship to pueblo,” Moraga said.

Sophie Girard is a second-year UC Santa Barbara student majoring in Communications and pursuing a minor in Professional Writing and Earth Science. She is a Web and Social Media intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.