By Faith Harvey

Creative writing programs in prisons lead to healing and a sense of redemption among incarcerated individuals, forging a sense of common ground and teaching them how to live more creatively, says author and activist Luis J. Rodriguez.

Rodriguez, who was the poet laureate of Los Angeles from 2014 to 2016, spoke earlier this month at the second installment of Too Much Information, a series run by US Santa Barbara’s Interdisciplinary Humanities Center.

“Differences are important, but acknowledging our similar situations allows us to help one another,” he said at the event, in which he was featured alongside his longtime friend Kenneth E. Hartman, a memoirist and director of advocacy for the Transformative In-Prison Workgroup, a statewide coalition of healing programs in prisons.

Rodriguez has been visiting jails and prisons in America, Latin America and Europe since 1981, teaching prisoners the art of poetry and creative writing. Hartman is one of his former students.

This past summer, UCSB graduate student Clint Terrell taught a course that included “How to Make a Poem Cry,” a collection of poems by prisoners of California’s Lancaster prison compiled by Hartman and Rodriguez. Terrell suggested the IHC to invite the two writers for a presentation.

Kenneth E. Hartman, left, and Luis J. Rodriguez speaking during the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center’s TMI event at UCSB. Hartman reads an excerpt from their book “Make a Poem Cry: Creative Writing from California’s Lancaster Prison.”

Hartman said that in an information-saturated world, prisoners in America experience information deprivation because the prison system keeps information out of the hands of prisoners deliberately. He spent 38 years as an incarcerated individual and said he faced this reality first hand. Hartman was originally sentenced to life for murder at age 19, but was pardoned by former governor Jerry Brown in 2017.

Hartman and Rodriguez met in 2007 inside Lancaster prison, where Rodriguez was teaching creative writing. Hartman calls Rodriguez a ‘hero’ of his and recalled that Rodriguez was one of the few people behind Lancaster’s cement walls to treat him like a human being.

“I remember when I first got into prison, the rehabilitation era from the 70s was ending,” Hartman said. He felt the criminal justice system did not think prisoners deserved a chance to overcome their worst moments. “There is a myth that people in prison are bad, or not fully human, and that they forfeit their own rights,” he said.

Rodriguez also had first-hand experience the prison system before he helped incarcerated people express themselves. He had confronted police, drugs, and juvenile hall. It wasn’t until an older mentor and friend of his offered help, resources, and connections, that he was able to transform his life by taking up writing and activism.

Rodriguez and Hartman both said those at greatest risk of incarceration are living in communities where there is poor education and no work, leaving few things to do besides finding drugs and falling into the wrong crowds.

In the 1970s there were 15,000 prisoners in California and only 15 penal institutions, said Rodruguez. Now, there are 34 institutions, and the population hovers above the 100,000 mark. Rodriguez said a large chunk of these numbers constitute youth.

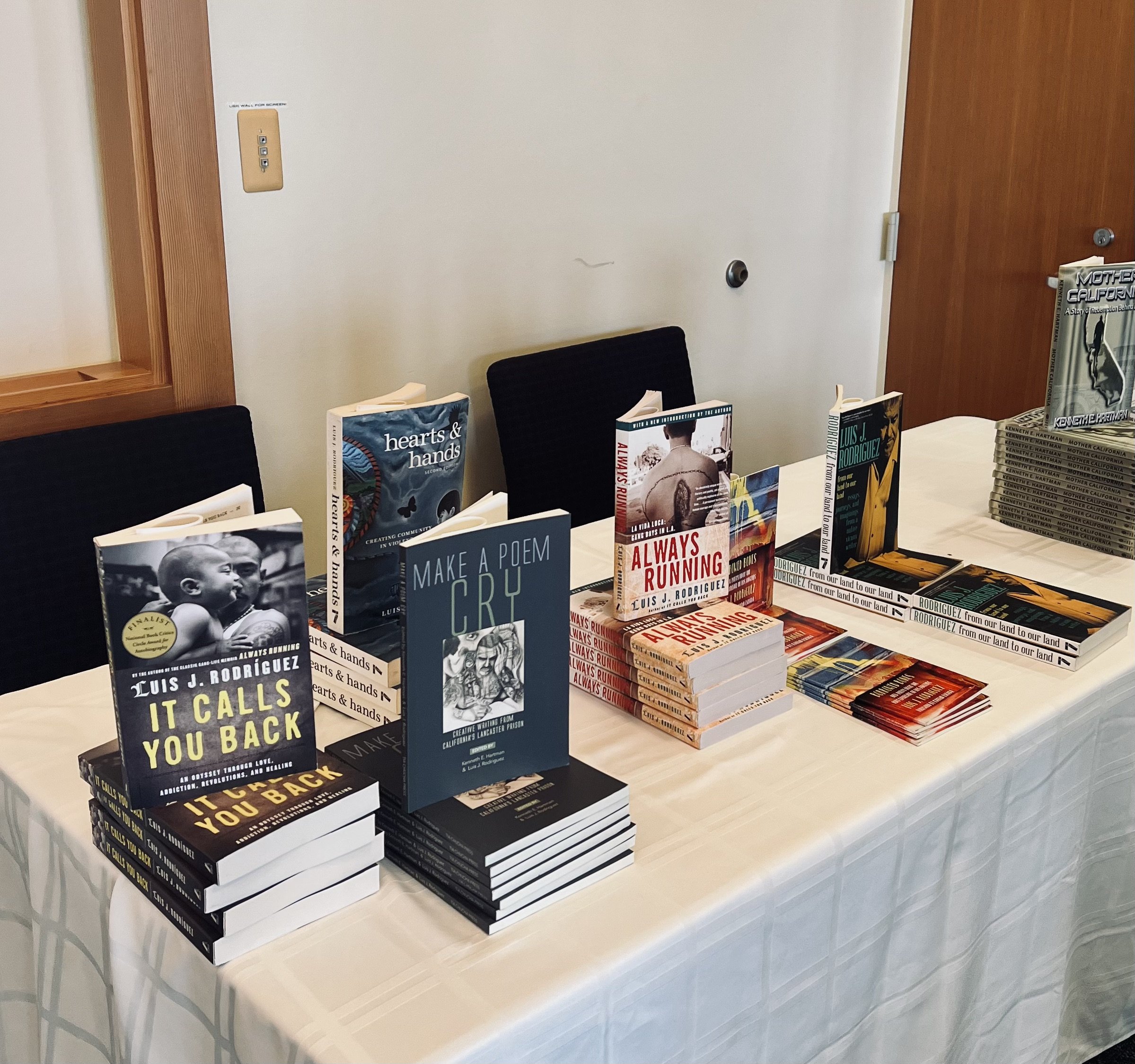

A collection of books authored or edited by Luis J. Rodriguez and Kenneth E. Hartman on display at the Interdisciplinary Humanity Center’s TMI Talk at UCSB.

What prisoners need most, according to both Hartman and Rodriguez, is healing. Poetry and creative writing is a huge support system for prisoners, they said. When Hartman began learning about writing in prison, a University of Southern California professor helped him and the others in his group express themselves.

Hartman recalled an instance where the professor told them they could write as well as university students. “The USC students can write a perfect paper, but what they lack is stories,” the professor told them. “You all have stories,” he said.

Hartman said poem submissions from Lancaster prison for the book “Make a Poem Cry” filled several boxes.

Hartman and Rodriguez ended their talk by reading excerpts from the collection. The final poem called “Heal” was written by a now-published and accomplished incarcerated poet named Spoon Jackson. The final line reads: “I must keep believing, I must keep believing in the power of healing.” It’s mantra that animates the lives of Rodriguez and Hartman, two former inmates now working together to impart lessons of compassion and creativity.

Faith Harvey is a third-year UCSB student, majoring in Communication studies and minoring in Professional Writing. She is a Web and Social Media intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.